A visit to the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in the East End of London on a cold February 2011 evening raised some fun musings on “long”. First, some background. The Whitechapel Bell Foundry casts bells, broadly of two types – big church bells comprise about four-fifths of the business and hand-held change ringing bells the remaining fifth. An unbroken line of master “founders” (in one sense) can be traced back to Master Founder (in both senses) Robert Chamberlain in Aldgate Ward in 1420, during the reign of Henry V, and 72 years before Columbus sailed for America. Billeter Lane in Aldgate was the original address, an etymology starting with “Belzeters” meaning bell-founders.

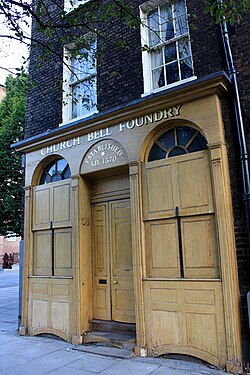

As with many late medieval enterprises, the Foundry was called by the name of the master founder which changed with each new owner. The concept of the foundry being a “company” dates from at least 1570, although formal incorporation only came about in 1968 and the name permanently changed to “Whitechapel Bell Foundry”. The company moved from Aldgate to Whitechapel in the early 1700’s under Master Founder Thomas Lester, taking over The Artichoke coaching inn built in 1670 which remains the heart of the premises today.

Worldwide exports began as early as 1747 to St Petersburg. Despite its small size, fewer than 30 employees, the Foundry is famous for having cast the Liberty Bell (1752) and Big Ben (1858). The factory floor is fascinating – a Stuart workshop in the modern era, where dung and goat hair for castings mingle with advanced electronic tuning equipment. The Hughes family took ownership in 1904 and family ownership continues today. Long Finance was there as part of a regular sideline in tours for City of London people, in our case Tower Ward Club.

What makes the bell industry interesting for Long Finance is change ringing peals. The English change ringing peal is the art of ringing a set of tuned bells in mathematical patterns called “changes”, with no attempt at melody. English change ringing dates at least to the early 17th century. If this sort of hobby interests you, the Chinese had an interesting variant three millennia earlier in bianzhong, rung sets of bronze chime bells which produce two tones each. True to its origins, as many a sleepyhead will attest, change peal ringing is popular in its homeland. Dove’s Guide for Church Bell Ringers (2007) lists 5750 ringable rings of bells in England, 201 elsewhere in the UK, 35 in Ireland, 12 in the wider British Isles but only a further 123 towers worldwide with bells hung for full circle ringing, mainly in Anglican churches in the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

English change ringing requires tuned bells, which is a highly demanding craft practised at half-a-dozen foundries, two in the UK and perhaps four others scattered round northern Europe. This may seem a large market for few foundries, but the product is annoyingly durable. During our tour the bigger market seemed to be refurbishing and fine-tuning bells from the 17th century. In the 18th century hand bell change ringing became popular as people started ringing the changes as a semi-serious pastime, and training for the tower bells. Naturally, firms ramped up hand bell production and new firms entered the market. The inevitable collapse of the change ringing hand bell bubble led to some firms foundering (sic) and the consolidation of the industry, in which the Whitechapel Bell Foundry participated, gobbling up a competitor or two.

Now to Long Finance. Seeking to learn from the experiences of long-lived institutions, Long Finance has noted the surprising persistence of ecclesiastical and academic communities. A number of people have pointed us to family businesses as well. At first glance, and 591 years later, the Whitechapel Bell Foundry seems to exemplify the longevity that family businesses can attain. However, it is also clear that the business depends on the communities of change ringers which in turn depend on the Anglican churches. If anything, perhaps the lesson from our tour is that slow changes in ecclesiastical communities can slow the lifecycles of related communities and the businesses that supply them.

So when you hear Big Ben on the BBC Evening News you can ponder the changes ringing on Long Finance.

[Sadly, the Whitechapel Bell Foundry could not withstand the economic headwinds and closed six years later in 2017.]

For More Information:

- Whitechapel Bell Foundry preservation, and more from Wikipedia on Whitechapel Bell Foundry

- Change ringing

- Billiter Lane

- Bianzhong

![039bc[1]](http://www.mainelli.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/039bc1-300x176.jpg)