Remarks to: the Company Of Watermen & Lightermen, on paddle steamer Elizabethan, on 8 July 2021.

Master, Wardens, Fellow Freemen, Ladies & Gentlemen. Thank you Master for inviting me to join our company on this evening, as we pay tribute to the immense service Colin and his team have given us over the past quarter of a century.

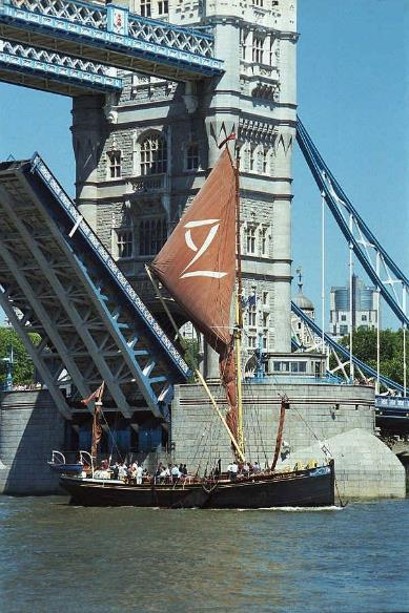

People in the livery sometimes ask why I am a craft-owning freeman of the Watermen & Lightermen. I am proud to say as a sailor and rower that water runs in my veins, and that having owned a Thames sailing barge, the Lady Daphne, for over two decades, some of that water in my veins definitely comes from the Thames. In fact, next week, I’m giving a lecture to the Guildhall Historical Association on the economic history of the Thames, the lighters, and the barges.

Continue reading