I thought we should start with a campaign photo. When the family took a skiing trip to Jackson Hole earlier this year, I wanted my daughters to see New York City for the first time. Naturally, as my firm, Z/Yen, compiles the Global Financial Centres Index, we had to take the girls to Wall Street, and thus I have my opening picture for the campaign from the land of my birth. There will be some better photos later (the ones without me in them)!

Broad Street Aldermancy – Nomination Papers Submitted

This morning I went round to the Election Office at the City of London Corporation to submit nomination papers for the Broad Street Ward Aldermanic election. All successfully registered and the campaign is now on. I am honoured to have the support of our retiring Alderman and former Lord Mayor, Sir David Lewis, and our three Common Councilmen, John Bennett, John Scott JP and Chris Hayward. To stay up-to-date with the campaign, simply click here.

If you are based in Broad Street as an elector (and if unsure, just ask) please do consider giving me, Michael Mainelli, your vote by postal ballot or by voting in person on Thursday, 4 July 2013, at Carpenters Hall, 1 Throgmorton Avenue, EC2N 2JJ from 08:00 to 20:00 – but whatever you do, please vote, the City needs a vibrant electorate. I walk through the Ward every day to and from work and would be delighted to discuss Ward business. Contact me by telephone 020 7562-9562, or via email michael_mainelli@zyen.com, or by post to Z/Yen Group, 90 Basinghall Street, London EC2V 5AY. For more campaign details see my campaign flyer – Michael Mainelli – Broad Street Ward Aldermancy Campaign 2013 – flyer

What’s In A Name?

This week’s ESMA & EBA report, “Principles for Benchmark-Setting Processes in the EU”, garnered headlines such as “EU plots to grab control of Libor from London”. Such sensationalism simultaneously leads to over-reaction and under-reaction. Libor is a known problem, but there are questions over other market indices for oil, steel, gold and other commodities. Surely five years into financial crises why shouldn’t the EU set out guidelines for robust indices upon which most markets depend? Yet I worry about state control and auditing of benchmarks. Some bankers claim they connived with regulators on Libor to look stronger than they were. Instead I would suggest a more ‘British’ approach – a published ISO or BSI standard on index governance and management, independently audited on quality, accuracy, timeliness and distribution in a competitive market. And the under-reaction? These financial reform proposals should be coming from London. If we’re losing our intellectual leadership perhaps we do deserve to lose the ‘L’ in Libor.

In CityAM 7 June 2013 – http://www.cityam.com/debate/should-london-be-concerned-about-eu-s-proposal-move-libor-oversight-paris

Broad Street Ward Aldermancy

I have decided to submit a nomination form to run for Alderman of Broad Street Ward. The Wardmote is scheduled for 3 July. If there is an election, then the vote will be on 4 July – hopefully auspicious. I am honoured to have the support of our retiring Alderman and former Lord Mayor, Sir David Lewis, and our three Common Councilmen, John Bennett, John Scott JP and Chris Hayward. More on this soon! But for now, some background information and a map.

I have decided to submit a nomination form to run for Alderman of Broad Street Ward. The Wardmote is scheduled for 3 July. If there is an election, then the vote will be on 4 July – hopefully auspicious. I am honoured to have the support of our retiring Alderman and former Lord Mayor, Sir David Lewis, and our three Common Councilmen, John Bennett, John Scott JP and Chris Hayward. More on this soon! But for now, some background information and a map.

Digital Migration

After many happy, though quiet, years running our own site using FrontPage, Mainelli.org migrates to WordPress with high hopes.

Business quotes

SIR – You began an article with the old saw “that half of all advertising budgets are wasted—the trouble is, no one knows which half” (“Change of track”, June 9th). The remark is frequently attributed by Britons to Lord Leverhulme, founder of Lever Brothers, and by Americans to John Wanamaker, who opened Philadelphia’s first department store. Though references to such a saying date from at least 1919, no authoritative reference has been found linking either man to it. This leads one to observe that at least half the attributions are false, the trouble is no one knows which half.

Professor Michael Mainelli

Executive chairman

Z/Yen Group

London

30 June 2012 – https://www.economist.com/letters/2012/06/30/on-charitable-donations-china-honduras-nepal-quotations-st-sebastian

Maria und Reinhold 2012

MARIA UND REINHOLD 2012

Bei dem Flusse Wern,

Vor dem duftend’n Tor,

Stand ein Reinhold Reuss

Und folgt er noch der Spur,

So sind sie zusamm’n gekomm’n,

In Pfersdorf will Maria wohn’n,

Wie einst, das Reussen Paar.

Wie jetzt, das Reussen Paar.

Eure beiden Schatten,

Sah’n wie einer aus,

Daß ihr so lieb euch hattet,

Das sah man gleich daraus.

Und alle Leute soll’n es seh’n,

Wenn wir bei der klaren Wern steh’n,

Wie einst, das Reussen Paar.

Wie jetzt, das Reussen Paar.

Schon schlug die EssUhr

Sie bläst den Entenstreich,

Es kann drei Kinder kosten

Schwiegersohn kommt gleich.

Da wünschen wir „Gut’n Appetit“

Wir sing’n gern für euch ein Lied,

Für euch, das Reussen Paar!

Für euch, das Reussen Paar!

Deine Schritte kennt sie,

Deinen zieren Gang.

Alle Abend brennt sie,

Doch mich vergaß sie lang.

Und sollte mir ein Leid gescheh’n,

Wer wird bei der Laterne steh’n,

Mit euch, die Reussen Paar!

Mit euch, die Reussen Paar!

Aus dem stillen Raume,

Aus der Erde Grund,

Hebt mich wie im Traume

Dein verliebter Mund.

Wenn sich die späten Nebel dreh’n,

Werd’ ich bei der Laterne steh’n

Wie einst, die Reussen Paar!

Wie einst, die Reussen Paar!

Christmas In Flames – “Firewood”

All right, my hearing’s not the finest, so when I heard Katie Duff singing “Firework” by Katy Perry at the annual Mainelli-Duff Christmas party, I had to have a rewrite, and dedicate it to her:

“Firewood”

for Katie Duffy

Do you ever feel like a piece of wood,

Feeling all the strain, of being lit again?

Do you ever feel, feel so flammable

Like one little spark, makes you combustible?

Do you ever feel already charred so deep?

Six feet under coal, but no one seems to sear a thing

Do you know that there’s still a match for you

‘Cause there’s a spark in you?

You just gotta ignite the light and let it shine,

Just own the night like a Costco buy

‘Cause baby, you are firewood,

Come on, you don’t blaze so good

You don’t burn so high -igh -igh

As you glow across the sky –y -y

‘Cause baby, you are firewood

Come on, you’re a waste of space

Inside a furnace -nace -nace

As you glow across the sky –y -y

‘Cause baby, you are firewood

Come on, you don’t blaze so high

You should want to die –ie -ie

As you glow across the sky –y –y…

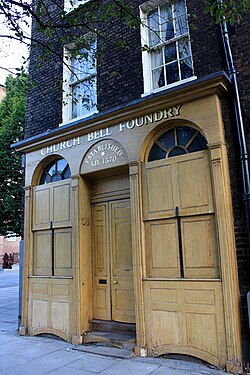

Ringing The Long Change

A visit to the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in the East End of London on a cold February 2011 evening raised some fun musings on “long”. First, some background. The Whitechapel Bell Foundry casts bells, broadly of two types – big church bells comprise about four-fifths of the business and hand-held change ringing bells the remaining fifth. An unbroken line of master “founders” (in one sense) can be traced back to Master Founder (in both senses) Robert Chamberlain in Aldgate Ward in 1420, during the reign of Henry V, and 72 years before Columbus sailed for America. Billeter Lane in Aldgate was the original address, an etymology starting with “Belzeters” meaning bell-founders.

As with many late medieval enterprises, the Foundry was called by the name of the master founder which changed with each new owner. The concept of the foundry being a “company” dates from at least 1570, although formal incorporation only came about in 1968 and the name permanently changed to “Whitechapel Bell Foundry”. The company moved from Aldgate to Whitechapel in the early 1700’s under Master Founder Thomas Lester, taking over The Artichoke coaching inn built in 1670 which remains the heart of the premises today.

Worldwide exports began as early as 1747 to St Petersburg. Despite its small size, fewer than 30 employees, the Foundry is famous for having cast the Liberty Bell (1752) and Big Ben (1858). The factory floor is fascinating – a Stuart workshop in the modern era, where dung and goat hair for castings mingle with advanced electronic tuning equipment. The Hughes family took ownership in 1904 and family ownership continues today. Long Finance was there as part of a regular sideline in tours for City of London people, in our case Tower Ward Club.

What makes the bell industry interesting for Long Finance is change ringing peals. The English change ringing peal is the art of ringing a set of tuned bells in mathematical patterns called “changes”, with no attempt at melody. English change ringing dates at least to the early 17th century. If this sort of hobby interests you, the Chinese had an interesting variant three millennia earlier in bianzhong, rung sets of bronze chime bells which produce two tones each. True to its origins, as many a sleepyhead will attest, change peal ringing is popular in its homeland. Dove’s Guide for Church Bell Ringers (2007) lists 5750 ringable rings of bells in England, 201 elsewhere in the UK, 35 in Ireland, 12 in the wider British Isles but only a further 123 towers worldwide with bells hung for full circle ringing, mainly in Anglican churches in the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

English change ringing requires tuned bells, which is a highly demanding craft practised at half-a-dozen foundries, two in the UK and perhaps four others scattered round northern Europe. This may seem a large market for few foundries, but the product is annoyingly durable. During our tour the bigger market seemed to be refurbishing and fine-tuning bells from the 17th century. In the 18th century hand bell change ringing became popular as people started ringing the changes as a semi-serious pastime, and training for the tower bells. Naturally, firms ramped up hand bell production and new firms entered the market. The inevitable collapse of the change ringing hand bell bubble led to some firms foundering (sic) and the consolidation of the industry, in which the Whitechapel Bell Foundry participated, gobbling up a competitor or two.

Now to Long Finance. Seeking to learn from the experiences of long-lived institutions, Long Finance has noted the surprising persistence of ecclesiastical and academic communities. A number of people have pointed us to family businesses as well. At first glance, and 591 years later, the Whitechapel Bell Foundry seems to exemplify the longevity that family businesses can attain. However, it is also clear that the business depends on the communities of change ringers which in turn depend on the Anglican churches. If anything, perhaps the lesson from our tour is that slow changes in ecclesiastical communities can slow the lifecycles of related communities and the businesses that supply them.

So when you hear Big Ben on the BBC Evening News you can ponder the changes ringing on Long Finance.

[Sadly, the Whitechapel Bell Foundry could not withstand the economic headwinds and closed six years later in 2017.]

For More Information:

- Whitechapel Bell Foundry preservation, and more from Wikipedia on Whitechapel Bell Foundry

- Change ringing

- Billiter Lane

- Bianzhong

Literature and the Arts – Final Dinner For The “Libraries, Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery Committee”

Chairman, Past Chairman, Aldermen, Ladies & Gentlemen

When John Scott asked me to address this Committee and its many supporters on behalf of the guests in honour of its Past Chairman at this farewell do, I was greatly honoured. Sidney Joseph (S J) Perlman wrote for the New Yorker and also for the Marx Brothers. A copy of Perlman’s 1929 book, Dawn Ginsbergh’s Revenge, was sent to Groucho Marx. Groucho sent Perlman a letter that said, “From the moment I picked your book up until I laid it down I was convulsed with laughter. Someday I intend reading it.” [quoted in LIFE, 9 February 1962] John Scott may wind up paraphrasing, “from the moment you stood up till the moment you stood down, we were convulsed. Someday we’ll get Lisa Jardine.”

[http://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2013/12/03/clockmakers-library-exhibition/]

I learned history in the United States. Thus I know two big historical facts about libraries. First, Benjamin Franklin invented the library. Second, we lost a lot of books during the Civil War when the great library burned down in Alexandria … Virginia. Imagine my surprise on arriving in London to find that libraries, even lending libraries, pre-date Franklin, who quite probably visited the Guildhall Library. Imagine my even greater surprise to find that the Virginians have rebuilt their Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Egypt.

We’re all book addicts. I read too much, carry a Camomile Street card, even founded and sold a multi-lingual children’s book publishing firm. I’ve browsed Harvard’s Houghton rare book library for Martin Luther’s thoughts on intellectual property, and toured the wonderful gem of Thomas Plume’s library in Maldon where my children were shown sixteenth century prints of rhinoceri. Our family checks out talking books from the Barbican while I delve in the Guildhall on Gresham College or the City digital archives on Thames sailing barges. Yes, we’re all addicts. Claire Scott and I sympathise with Groucho Marx – “I find television very educational. Every time someone switches it on I go into another room and read a good book.” Though an art philistine, I’m forever telling friends to borrow my visitor’s card to the Guildhall Art Gallery. A while ago, as one wag put, “the Guildhall Art Gallery was the only public art gallery in London where everyone got a private viewing”. Today, thanks to this Committee’s work, the Gallery reaches more and more people as the City opens up to visitors, rather than closing in due to the financial crises.

Yet … asking friends about libraries for this lecture elicited immense support, but a paucity of recent visits. Some years ago I hosted a dinner for a man with a strange accent, Loyd Grossman. As well as his sauces with a distinctive voice, Loyd is known for his work on museums and questioned whether museums were “Temples of the Muses or Temples of Amusement”. Everyone loves museums in the abstract, but in practice? Last year our family added a Kindle and an iPad last year to our menagerie of gadgets. Both have filled up with our-children-ought-to-read-these books Elisabeth and I treasure. And this affects libraries. Libraries and archives are loved in abstract, but attendance and usage drift in these days of “never judge a book by its movie”. [JW Eagan]

Perhaps libraries and archives are never more loved than as metaphors. Jorge Luis Borges was director of the Argentine National Library. He remarked, “if I were asked to name the chief event in my life, I should say my father’s library”. Borges’ famous short story, The Library of Babel, postulated a vast library containing all possible ‘410 page’ books, inspiring numerous philosophical musings, such as how libraries explain Bertrand Russell’s paradox on mathematical sets – where do you catalogue the catalogue of all catalogues that don’t list themselves?

The British statesman Lord Palmerston must have visited many libraries to become an expert on the enigmatic Schleswig-Holstein problem of the mid 19th century. Palmerston said: “Only three people have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business – the Prince Consort, who is dead – a German professor, who has gone mad – and I, who have forgotten all about it.” In the age of the internet, libraries, archives and art galleries everywhere pose riddles of Schleswig-Holstein complexity. According to W V Quine, the renowned Harvard philosopher, Borges’ infinite library can be created simply by writing a dot on one side of paper, a dash on the back, and then randomly flipping till the end of eternity. Bits and bytes are our challenge. Our pressing paradox is that until some desperately distant time in the future, we need to preserve the past today.

Libraries and archives serve at least three functions – building communities of learning, providing information services, and supporting research. All of these are important to us, and all are in flux. But I would like to emphasise a fourth function that this committee exemplifies. Experimentation. Notwithstanding our shared fondness for cellulose information storage, this committee’s legacy will be its experiments. Whether trialling DVDs or internet access, testing new working methods, building European Visual Archives, or striking innovative deals with Ancestry.co.uk, this Committee has shown daring. And while he or she who dares does not always win, they are remembered. Libraries and archives will change – and this Committee has helped them learn how.

Seneca believed in this form of remembrance: “Why do you ask, how long has he lived? He has lived to posterity.” [“Quid quaeris, quamdiu vixit? Vixit ad posteros.”] (Lucius Annaeus Seneca), Epistles (XCIII) Preservation is key, but your true legacy is what you dared to try for posterity. Sometimes posterity is high-brow, from new insights on the origins of science to rediscovered musical scores. Sometimes posterity is low-brow – C J Sansom’s best-selling crime series set in the reign of Henry VIII features a hunchbacked lawyer in Lincoln’s Inn, Matthew Shardlake. Shardlake has to rely on the Guildhall library to solve cases. Someone in the 16th century experimented with letting lawyers in. Now that was daring.

We’ve had a great evening with fantastic food, wonderful music and fine hospitality. This is not a wake, more a celebration around a blazing phoenix – I expect much to arise from this Committee’s legacy; so I shall end with a quote from Teddy Roosevelt that exhorts your successors to experiment even more – “Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs even though checkered by failure, than to rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy nor suffer much because they live in the gray twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.”

May I ask all guests to be upstanding as I propose a toast to our hosts – “To the Libraries, Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery Committee – Literature and the Arts.”

![039bc[1]](http://www.mainelli.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/039bc1-300x176.jpg)