What a most interesting talk to give. My dear friend, Robin Sherlock KCLJ MA, former Chief Commoner of the City of London Corporation, asked me to speak at the Ladies’ Dinner of The Dulwich Club where he has been Senior Steward the past year. The Club, founded in 1772, is one of the oldest dining societies in the world. Elisabeth and I found the entire evening a delight. Haberdashers’ Hall was rebuilt after the fire of 1666 and the bombing of WWII, yet the Company made a brave decision to open one of the most tasteful modern halls in 2002, a true architectural gem opposite St Barthomew’s.

Giving a talk to The Dulwich Club was no easy task, as they’ve heard them all before. I was a bit trepidatious, particularly as the Junior Steward, Bruce Purgavie made clear my ignorance of football yet expected me to show some rocket science skills the night after Guy Fawkes. What can one say? Well, this was it:

Sir Thomas Gresham: Tudor, Trader, Shipper, Spy

The Dulwich Club – Ladies Night Dinner

Haberdashers’ Hall

Thursday, 6 November 2014

“Senior Steward, Junior Steward, my Lords, distinguished Guests, Ladies. When Robin suggested that I have a dinner with the Ladies of London’s most exclusive dining society, I was particularly pleased. When he suggested I bring along my Lady Elisabeth, while delighted of course, I began to realise it wasn’t my looks – I would be lecturing for my dinner on behalf of the Visitors.

Robin suggested I do a serious talk, after all the jokes, about being a newish Alderman, so I naturally thought of ward disputes, governance, compliance, and endless committee meetings to share with you. Robin wondered if perhaps there was something slightly more interesting, so let me share with you one fun project of the Joint Grand Gresham Committee – a biography on Sir Thomas Gresham: Tudor, Trader, Shipper, Spy, born 1519, died 1579.

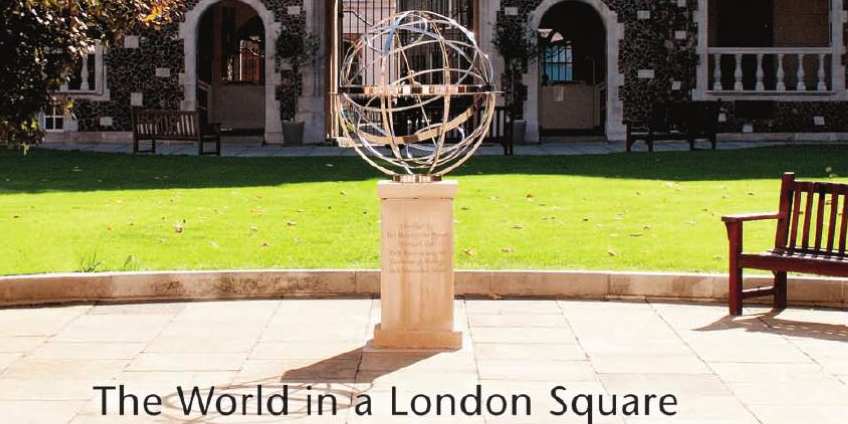

When I was a boy two-door was what you bought when you couldn’t afford four-door, but Gresham served four Tudor monarchs, managed to keep his head, and all the while made money. Lots of it. He probably died comparatively wealthier than Bill Gates or Warren Buffett. 435 years later his legacy still generates millions for good causes. We have Gresham Street. We have his statue a few hundred yards away on Holborn viaduct, another at the Royal Exchange. We have his Tower 42 Mansion site, Osterley Park, Boston Manor. His grave at St Helen’s Bishopsgate. We have grasshoppers everywhere – on the top of the Royal Exchange, at 68 Lombard Street, on stained glass windows.

Gresham was born on Cheapside and attended St Paul’s School and Gonville College, Cambridge. In 1543 he went to Antwerp to make his fortune as a Mercer. Antwerp then was very cosmopolitan and large for the time, with a population approaching 100,000, double London or Rome. Just 25 merchants accounted for half of London’s cloth exports, and the two biggest exporters were the brothers John Gresham and Richard Gresham, Thomas’s father.

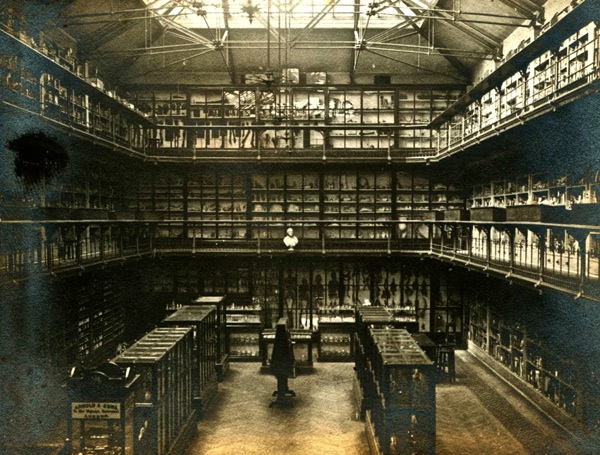

Gresham imported from Antwerp the idea of a ‘bourse’ or ‘exchange’ for intangible items such as ship voyages and insurance. Incorporated into the 1571 Royal Exchange were 150 small shops, called The Pawn, London’s first shopping centre. From within St Martin’s Goldsmiths he experimented with fractional reserve gold stores, cornering markets, and insider trading. His Will, enacted upon his death in 1579, created Gresham College and challenged the ‘Oxbridge’ oligopoly in higher education.

We are commissioning a biography which we hope to publish on the quincentenary of his birth, 2019. But what does a Tudor have to say about contemporary issues? I thought I’d ‘channel’ Gresham on three questions today:

1 – what should we do about our banks?

2 – what should we do about our currency?

3 – what should we do about Europe?

1 – What Should We Do About Our Banks?

Gresham was probably one of the first goldsmiths to issue more certificates for gold in the vaults than he had. Our modern economic terms are fractional reserve banking or leveraged banking. So rather than letting banks such as RBS in 2008 lend 42 times what they had in the vaults, Gresham would probably recommend tight control over leverage. He might have recommended that our quantitative easing continue to the point that our banks were lending little more than they have in their vaults.

2 – What Should We Do About Our Currency?

Gresham explained to Elizabeth I that because Henry VIII and Edward VI had replaced 40% of the silver in shillings with base metal, ‘all your fyne gold was conveyed out of this your realm.’ Colloquially expressed as “bad money drives out good”, Gresham’s Law was attributed to him in 1858 by a Scottish economist. Two awkward bits – the Law is the reverse, “good money drives out bad”, and Gresham’s Law was not his; it was noted much much earlier by many, starting with Aristophanes. The Nobel economist Robert Mundell rephrased Gresham’s Law more properly as “cheap money drives out dear money only if they must be exchanged for the same price”.

In 1551 Edward VI appointed Thomas as Royal Agent in Antwerp. A clever and shrewd dealer, Gresham reduced royal indebtedness from £325,000 to £108,000. He reduced the national debt by two-thirds in nine months. Under so-called ‘austerity’, UK national debt has grown over the past four years by a third. William Cecil put Gresham in charge of recoinage in 1560. To his, Elizabeth’s, and Cecil’s credit, within a year debased money was withdrawn, melted, and replaced, with a profit to the Crown estimated at £50,000.

Gresham stood for an independent pound sterling. He certainly wouldn’t have sold off the national gold reserve. More interestingly, he might also have supported an independent London currency.

3 – What Should We Do About Europe?

A Gresham ship from 1570 was re-discovered in the Thames in 2003; its cannons inscribed with grasshoppers and marked ‘TG’. There are tales of bullion concealed in bales of pepper or armour. Gresham was clearly a “merchant adventurer” with a network of European agents, though the sobriquet ‘arms-dealer’ might equally apply.

The Royal Exchange began as his father’s idea, but the idea behind the exchange and the shops was that London prospers when all who come for exchange are treated fairly.

Gresham was a free trader and Europhile, yet also a realist and a spy, committed to engaging with Europe, vigorously, but for mutual and selfish benefit.

Hop To It

I must end on grasshoppers, in two ways – the family symbol and Kung Fu. The Gresham grasshopper first appears in the mid-1400’s. According to family legend, the founder of the family, Roger de Gresham, was abandoned as a baby in long grass in North Norfolk in the 13th century. A woman’s attention was drawn to the foundling by a grasshopper. While a beautiful story, a more likely explanation is that the Middle English word ‘gressop’ for ‘grasshopper’ resembles ‘Gresham’. I think the Royal Exchange may have taken the theme too far – if you look on the south side just now it reads, “luxury shopping”, but the “s” has temporarily fallen off. Luxury hopping?

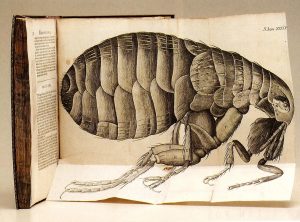

And Kung Fu? Well grasshoppers, you’ll remember David Carradine and the 1970 television series – ‘grasshoppers’ are students. Gresham believed in the power of education for all. His Tudor Open University spawned ‘The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge’ after a 1660 lecture by Sir Christopher Wren, then Professor of Astronomy. Today Gresham College hosts over 130 physical events per year free to the public, distributes recordings under a Creative Commons licence, and provides millions of people with lecture transcripts and recordings via the internet.

A century after Gresham’s death Samuel Pepys enjoyed Gresham’s legacies, listening to one of the professors ‘sufficiently learned to reade the lectures’, then strolling through the Royal Exchange afterwards in search of a gift for a loved one, as can you today well over three centuries later. We’re pleased to be setting out on the first proper biography and I hope you feel he is a worthy subject. What I might ask you to do is look around the City and wonder at how we ourselves could leave a comparable legacy for the next half a millennium. We, your grateful guests, know the Dulwich Club will be full of enthusiastic ideas. Thank you!”

And for even more…

Michael Mainelli and Valerie Shrimplin, “Sir Thomas Gresham: Tudor, Trader, Shipper, Spy”, London Topographical Society Newsletter, Number 79 (November 2014), pages 3-6.